When I was a little girl, I lived in a small town in Georgia. Everyone who lived there knew their neighbors. Not just the ones right next door, but up and down each street. It was a homey place to grow up in, a safe place where people looked out for one another and one anothers’ kids.

My extended family has lived in the same area of Georgia for generations. We were a settled bunch with family traditions. Every Sunday while my parents were still married, we, along with cousins, went to my Grandmother’s house after church to eat Sunday dinner. We stayed a good long time, longer than I wanted to sit and talk like the adults did, so I would entertain myself as best I could since my brother and sister rarely wanted to play with their baby sister.

When I was really young, a little boy named Johnny lived just two houses down the street from my grandmother’s house. In fact, I liked him so much I named one of my kittens(one of the many) after him. The house he lived in was not like mine. It had dirt floors, and the screen door on the front entry could be lifted up so two little kids could step over the base and enter without ever opening the door. I thought that was so cool and wished my house had such a wonderful door. I’m not sure what happened to Johnny. He moved when I was still pretty young. But I do remember my mom and grandmother talking between themselves when they thought I wouldn’t hear about how letting me go play with him might not be a good idea. I didn’t understand why.

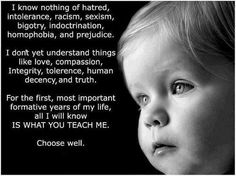

I understand now, however. When children are little, they don’t see poverty or skin color, or socioeconomic status. They only see people. I knew Johnny was fun to play with. That’s all that mattered. What his position in society was didn’t matter at all. When I taught the book To Kill a Mockingbird to my sophomores, I often remembered Johnny, especially when Scout tells Jem, “I think there’s just one kind of folks. Folks.” Scout was still too innocent to understand why Jem thought there were different kinds of people in the world. Of course he was no longer innocent after seeing what happened to Tom Robinson, the black man wrongly accused and convicted of raping a white woman. Jem understood what Scout didn’t yet, that there was injustice in the world.

Another thing that struck me when I taught that book was the difference between how I see the world and how my students did. When we studied that book I had to explain racism and Jim Crow laws to them even when they had learned about it in history class. Often as we read about how some people treated Tom Robinson or how they treated his wife or any other unjust incident in the book, they would ask me, “How could anybody treat others that way?” My heart would break when I explained, but at the same time I rejoiced that they saw no reason to treat anyone of a different race or sex or socioeconomic status differently. I am grateful kids don’t view others the way adults do that they haven’t yet lost their faith in humanity.

We learn prejudice in all its forms. We learn how to treat people from our elders and from those we associate with. Sometimes we treat others poorly because we bow to peer pressure. Sometimes we are afraid of what treating someone differently might say about us. Whatever the reason, we don’t live up to “the better angels of our nature.” Children are not prejudiced. Somewhere along the way they learn to be. But we don’t have to remain that way.

I am guilty of treating others poorly, of making my prejudice known. One of the biggest regrets in my life is that one of my best friends in college, who was overjoyed at marrying the love of her life, felt she couldn’t tell me about him or her marriage because she was marrying an African American man. She didn’t know how I would react. That said volumes, not about her, but about me. To this day I am embarrassed about that, but her telling me had a profound impact on my life. I woke me up to my own prejudice and made me examine the way I thought, which I’m happy about.

When I married my husband, I also married the Marine Corps, a color blind society if ever there was one. I learned to get along with people from all over the United States and all over the world: the Philippines, England, Mexico, Honduras, Haiti. Everywhere. We lived in many different states, but the one thing that united all of us was that we were living a military life. Race didn’t matter. Neither did anything else. We endured together.

When I was becoming certified to teach, I started out in the public schools in Florida and even did some practicum work at a public high school in Milledgeville, Georgia. I taught all kinds of kids, white and black and brown, from every background imaginable. I started my teaching career at the largest population school in Wisconsin and taught at a small rural school in the middle of Wisconsin. Even here I have taught white kids, black kids, Hmong kids, Hispanic kids, and kids from other countries. The one thing they all have in common is being young men and women who want to be successful and to be taken seriously by adults. Race, socioeconomic background didn’t matter. They wanted me to treat them fairly and not to abandon them when they needed someone to talk to. They wanted praise when they succeeded and help when they failed. Isn’t that what we all want?

I have learned much in the course of my life which has humbled me. Mostly what I’ve learned is that all people, no matter where they come from, are children of God and should be treated with respect. I haven’t always done that, but I try to. I don’t have all the answers to the terrible things happening in our country right now. I wasn’t even sure I wanted to write about this topic because I feel overwhelmed and sad and confused, and I’m sure someone will not like what I’ve said. I don’t want to be part of the controversy or take away from anyone’s loss. Like everyone else struggling to understand it all, I’m just trying my best to make sense of what feels senseless and wrong and tragic.

We need to discuss so much concerning race relations, but those conversations are hard. They are hard to have even with our friends. No one wants to be called a racist, so often people don’t have the hard conversations to understand. We become defensive rather than understanding. I’ve never even talked about race with my college friend, but I’m sure she has a lot to tell me and much I need to hear about her children and how they’ve been treated and how her husband has been treated.

In these discussions I’m afraid we won’t hear what needs to be heard because people are so entrenched in who we think we are, the outer trappings of our identities rather than the inner workings of our hearts. About six or seven years ago I was talking to Pastor Jim, a former pastor at my church about an unrelated concern, but he told me something that has stuck with me ever since, and I often use it as a guide to figuring out what to do in difficult situations. I think it applies to this particular time and issue. He said,” If we err, shouldn’t we err on the side of love?” Indeed.

If we could get to know our neighbors, not the ones we live right next door to but the ones we ordinarily wouldn’t talk to, maybe we could make a difference. If we could see each other with the eyes of a child, maybe we would think, like Scout did, that “There’s just one kind of folks. Folks.” Our skin color doesn’t matter. How much money we make, or don’t make, doesn’t matter. Our ethnicity doesn’t matter. Those things give us character, but they aren’t who we are. Who are we without those things? Who are you? Who am I? All of us deserve dignity and respect. All of us deserve to be heard. All of us deserve to be safe.

I am challenging myself this week to do something small, something manageable that might make a difference. Many small things add up to something big if enough people do them. When you go out into the world this week, introduce yourself to someone you don’t know. Make a friend. Smile at the person next to you in line at the grocery store. Pay for someone’s coffee or food at the drive through. Be a blessing to someone in some way. We cannot allow this crisis to divide the good people of this country. Abraham Lincoln in his First Inaugural Address said this about anther moment in time that nearly destroyed our country: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection.” Let’s make an effort to see each other as neighbors and take care of each other as such. Let’s also make our neighborhoods homey places again where nothing matters but being together, where folks are just folks.

I love you Shannon! Over the last 24 hours I have read ALL of your blog posts, many of them for the second time. I had forgotten about this one. I was in Athens this past weekend and actually cried, tears of joy, for times gone by. Despite time and distance, I still feel as close to you as I did on those late nights at 1111 South Milledge Ave. I can’t wait to read your book and proudly proclaim ” That is my forever friend”.

I love you too, Cindy! I am honored that you would read what I’ve written, and I mean that with all my heart. I miss your friendship so much. We had some wonderful times together and some trying ones too. I’m so blessed to have had you to share them with. We will ALWAYS be friends, no matter what. 🙂